Facing pushback while driving engineering initiatives: most common reasons, how to prevent and handle.

You work on a Big Improvement: rewrite backend on Go, move services to AWS, change a task tracker — something that affects multiple people's day-to-day work.

And then the initiative faces a pushback.

How much it hurts depends on when you encounter it: rejected proposals feel more bearable than having to throw away the nearly finished work you've been doing for months.

How to prevent it?

I have repeatedly found myself on both sides of the fence — as a proponent of innovations and as a member of the sceptical camp. Now, I am pretty sure that Big Improvement's future entirely depends on its author: how they prioritise different kinds of work, address concerns and adapt to feedback.

Let's figure out how to deal with yours

For the purpose of this article, I assume that:

1) you did your homework and know that your company will benefit from this initiative

2) you are open to feedback and ready to adjust if needed

Why technical initiatives fail

Ask yourself: why would anybody reject a good initiative? Assuming nobody is malicious, the answer is obvious – they do not think it is good. But why?

There are many possible reasons:

Some of them are more frequent than others, and I want to highlight these three as the most common:

- People do not believe you can reach promised goals

- People tried what you built and did not like it

- People disagree that the problem is worth solving

Let's see how you can prepare to face each of them.

Reason 1: People do not believe you can reach promised goals

Imagine a medieval kingdom that has been terrorised by a gigantic dragon for centuries. The dragon mercilessly burns the fields with the best crops, devours cattle, and kidnaps the most beautiful (by dragon standards) princesses.

You, a foreign knight, come in armour and on a white horse and ask for thirty armed men and two bags of gold to finish off the dragon forever – something that many have tried to do, but no one has yet succeeded.

What do you expect to hear back?

How it may sound to you

Why do you think it would be more performant and easier to maintain? Are you sure? I'm not sure...

– Carina

What the root cause is

The longer a problem exists, the harder it is to believe that somebody can solve it.

Especially if there were many unsuccessful attempts in the past.

Psychologists call this effect "Learned helplessness" and suggest that it can spread like a virus, infecting individuals, teams and organisations. Collectives that catch it become inert and pessimistic — it requires enormous effort to overcome the dominant belief that nothing can be done.

How to deal with it

Scepticism is contagious. Therefore, it is easier to prevent it than change many people's mind. But you cannot do it with bare arguments.

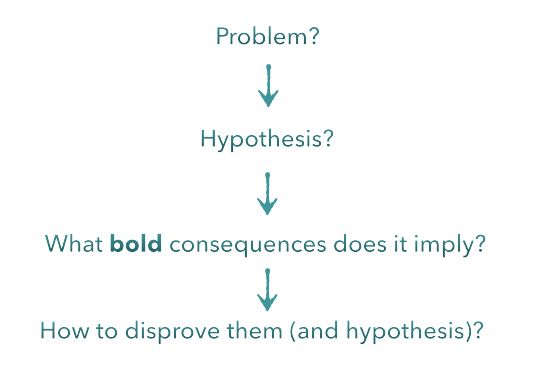

Instead, you can benefit from applying some principles of the hypothetico-deductive method:

- First of all, you agree on a definition of the problem with those who already tried to tackle it

- Then, you propose your idea – something that should solve the problem

- Together, you deduce the list of consequences: what would the solved problem look like.

The list may be pretty long, so it is worth focusing on the riskiest cases: if the hypothesis is incorrect, you want to know it as soon as possible - And finally, you agree on the list of experiments that may help you to disprove the consequences and fail fast

If it looks too abstract, let me bring a more concrete example:

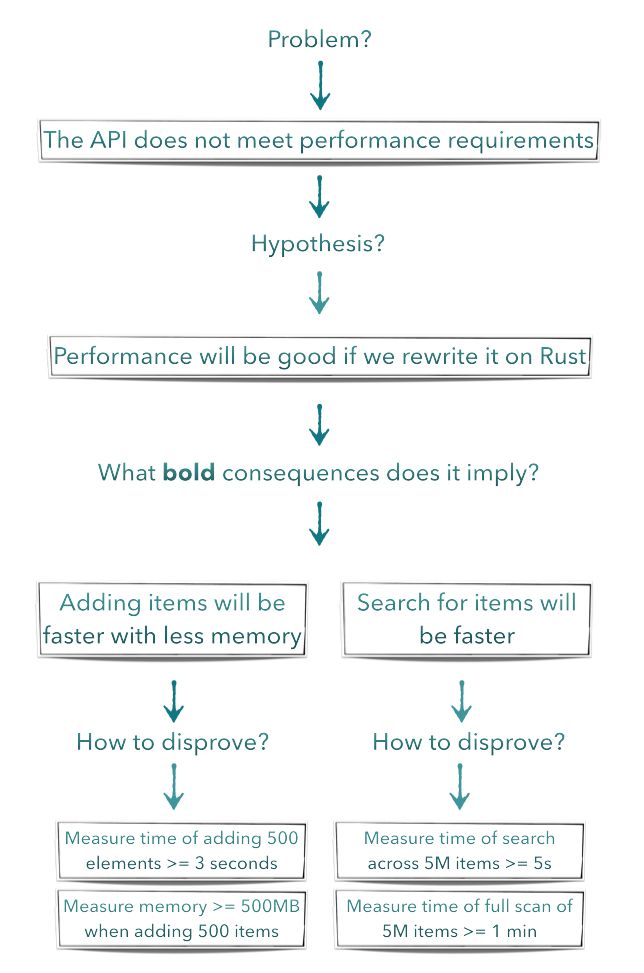

In the example above, we propose using Rust to solve existing performance problems.

Instead of reasoning whether it would work or not, we identify parts of the system with higher chances of performance problems, agree on how failure would look like and design the experiments that may reveal the shortcomings.

Even though it may sound straightforward, it is common to see two other approaches which do not end up well:

- a proposal faces reasonable scepticism and does not get through not being backed by solid evidence

- engineers either do not identify or do not prioritise risky cases and then have to throw away a large amount of work

But anyway, it was a pretty easy one – time for the more interesting case!

Reason 2: People tried what you built and did not like it

This happens a little bit later, when you think you built something good enough for others to use.

You prepare a polished demo that fulfils all expectations and makes everyone's hands hurt because of incessant applause:

But when others start using it... well, this happens:

How it may sound to you

I like the old way better.

Yes, I needed to change the code in five places.

Yes, the code was hard to test.

Yes, it was less performant.

But at least I could get it working because I knew what to do.

Now, I have no idea what's going on, and it all keeps breaking!

Can you de-engineer it back?

— Marcus, the early adopter

What the root cause is

There are several possible causes, and in most cases, they occur together:

- Not enough documentation

Writing docs is never the top priority during a turbulent time of building something new - Unexpected bugs

After the flawless announcement, people may develop high expectations and forget that this is only the first version - Unfinished implementation

It may be frustrating for early adopters to start working with the new thing and then stumble upon a blocker - Rosy retrospection

In psychology, rosy retrospection is the tendency to recall the past more positively than the present (even when the facts suggest the opposite)

How to deal with it

Ensure that people have the best possible experience working with a new system from day one.

It would be ideal if you provide:

- Documentation with exhaustive examples

- A list of known bugs and the current state of the roadmap to manage expectations before people start using it

- Support during development so that you can answer questions as they arise and unblock people

If it is impossible to do all of this because you don't have many resources, I would recommend keeping other people away from this version until it meets all criteria. The quality of the first impression means much more than time.

You may have valid reasons not to wait, e.g. when other engineers want to start building something else on top of your system while it is in development. All situations are different, but my suggestion for this case would be to pair with them until they have necessary context.

Reason 3: People disagree that the problem is worth solving

Imagine yourself in a group of bright scientists trying to invent powerful yet affordable quantum computers.

At some point, your experiments pay off, and you find the way to manufacture inexpensive quantum chips –– with them, even smartphones would vastly outperform existing supercomputers from the IBM labs.

However, there is one minor drawback. Its architecture is absolutely incompatible with what we have nowadays, making most of our computer science knowledge redundant. Needless to say, some developers may find having to learn all from the beginning a little unfortunate.

To say the least.

How it may sound to you

What do you mean by 'automated releases'? All you need to do is to log in to the production machine, download new code and run three commands – I can tell you which ones.

You call it a problem just because you were not here 12 years ago!

– Dr Nicolas Peter, PhD

What the root cause is

To discuss the root cause, we need to consider two separate cohorts:

- Those who are used to the current way of doing things

- Those who somehow benefit from it

The first group's reasoning is pretty obvious (just make the transition smooth for them); therefore, I will focus on the second one.

Nobody introduces inefficient systems on purpose. At least, these situations are pretty rare.

Quite the opposite – people usually have good intentions:

- They see a big problem (same as you!)

- They implement a solution (similar to your Big Improvement!)

- They become experts in it.

In time, the solution loses its appeal: it does not satisfy new requirements, there are open source analogues which do the same, and so on. It is time to replace it with something better, but it will imply throwing away all hard-earned knowledge, taking off an expert hat and having to learn something new.

Besides, the experts know the current version like the back of their hands and see all arguments as exaggerated.

How to deal with it

The traditional way of constructing an argument almost guarantees resistance. This is what I call a traditional way:

- You state the problem

- You demonstrate evidence of why this problem is vast and needs solving

- You describe how bright the future would be if you solved this problem

- You explain how you are going to do it

For all its factuality, this approach is devoid of any compassion: you go to the people who built the thing, to the people who use the thing, and to the people who have become experts in the thing and tell them not only that the thing is terrible, but that it has become a huge problem and needs to be replaced immediately.

The alternative approach acknowledges the history of an existing system and focuses on what changed since it was initially created. This can help build a foundation for productive collaboration with the current group of experts and get them on board.

This list of questions can help have a constructive conversation with the experts:

- What were the initial goals of the system?

- Does the system still satisfy all its initial requirements?

- Which parts of the system are you (the expert) not happy with?

- Which parts of the system have degraded in time due to technical debt and negligence?

- Have we received new requirements that the system does not meet?

- How can we make it right together?

This approach allows you to join forces with knowledgeable people to find out much more about current and potential use cases, identify hidden problems, and not repeat old mistakes. Experts, in turn, can retain and update their experience after replacing the existing system. Win-win.

One final tip

Rejection can be painful. Fear of rejection is real.

You may want to avoid this by not letting anyone into your plans until everything is perfect.

Do not fall into this trap because building what nobody needs is much worse than facing a pushback.

Instead, be wise in driving your initiative because its future depends on you: how you identify stakeholders, prioritise different kinds of work and adapt to feedback.

Credits for the cover photo go to Matt Ridley (photo from Unsplash)